Is Toronto a waterfront city? I grew up not too far from Woodbine Beach and whenever my mother took me to play in the sand, she often cautioned me “Don’t go in the water! The lake’s not clean.” The idea that Lake Ontario isn’t for swimming is burned into my subconscious. Nearly two decades later and plenty of evidence that the lake is generally safe, I still hesitate before jumping in. In my experience, Toronto is a city related to the waterfront but not a waterfront city. The city has spent decades trying to change that but the Gardiner is our roadblock.

The Redevelopment Plan

In 1968 Toronto came out with a waterfront redevelopment plan with high hopes in its ambition. Upon its completion, Ontario Place served as a kind of exhibition for an entirely new city built on top of Lake Ontario. Its planned successor, Harbour City, would make use of the floating islands debuted at Ontario Place to construct a high density, mid rise, mixed income, walkable, mixed use, transit-oriented neighbourhood on the water. People had become concerned that car dependency had let cities become too segregated and inhuman. These concerns remain the kind of things planners try and get at with projects today.

What would have been particularly interesting was the effort to incorporate canals and water travel into the plans. Think of Harbour City as a kind of space age Amsterdam. While there is boating in Toronto, there isn’t much of a boating culture when compared to a city like Boston. Perhaps Harbour City may have chartered Toronto a new course.

ADVERTISEMENT |

Harbour City

Toronto has a long tradition of filling in the lake to make room for industrial space. Now it was going to use infill to put people in the centre of the water, as opposed to pushing the water away. The Gardiner Expressway and railway tracks had turned much of the shoreline into a transitional space, a place people didn’t go but passed through. Industry had long since dried up and left plenty of abandoned buildings. For those who wanted to make use of the downtown lakeshore, there was plenty to deter them. Harbour City hoped to re-orient Toronto back to the water by turning it into a destination and neighbourhood in its own right.

Characteristic of the time, Harbour City was futuristic and it was going to be done a grand scale. I can’t do the plans justice like an old promotional video does. Urban guru Jane Jacobs said that Harbour City was “probably the most important advance in planning for cities that has been made this century.” I think she was right. Harbour City sought to use state of the art design and architecture to reconcile Torontonians with their natural waterfront environment while seeking to address modern city planning concerns.

Harbour City: Cancelled

There were two factors that lead to the cancellation of Harbour City. One was environmental. People were concerned that increased usage of the lake would only add more pollution. In the words of one concerned resident “the first thing to do is to clean up the present pollution on the island and make that parkland much more useful and a better place for the people who currently live in the city, those who do not escape now to Muskoka and their cottages…”

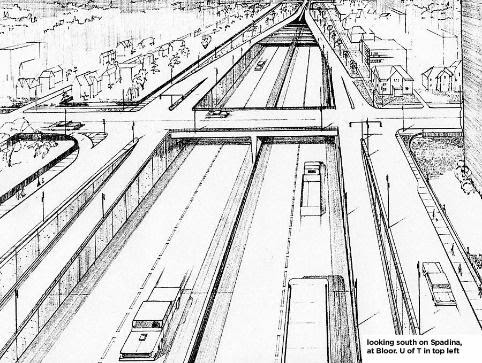

The other factor is one of great irony. Somehow, the fate of Harbour City was tied to the Spadina Expressway, a highway that would have extended the Allen down along Spadina, terminating near the University of Toronto. It was a project that was rightly cancelled as it was revealed to offer minimal traffic improvements while destroying a historic section of Toronto. What did it have to do with Harbour City? I’m not sure, but one speculates that the Province was worried about the outcry over pollution and didn’t want to get into another fight with downtown activists.

ADVERTISEMENT |

Can The Government do Two Things And Not a Third?

Frankly, the cancellation of Harbour City seems a little silly. Couldn’t we have cleaned the lake, cancelled the expressway, and built Harbour City? Surely, the government can do two things and not do a third thing. Sounds easier than doing, heaven forbid, three things. My foolishness is apparent here because easier still is doing nothing and that’s what we did.

Plan of the Spadina Expressway by Casa Loma. Source: Source -Unbuilt Toronto – Toronto Archives

What Did Harbour City Become?

What was built does have similarities to Harbour City. It’s a mixed use, mixed income (don’t forget there are plenty of co-ops among the condos), walkable, and transit-oriented community. On the other hand, it’s nothing but high rises and fairly conventional in terms of its relationship to the water. Many have scoffed at condo living, suggesting it lacks soul. Keep in mind the Harbourfront is still quite young and unlike older areas of the city, has had less time to develop the community bonds that make a neighbourhood unique. It’s only recently become common to see families living in the condos everyone assumed would house single young professionals. It was only in the past few years that the waterfront has gotten its own elementary schools. It’s a livable place and new projects continue to pop up.

Does The Gardiner Threaten The Kind of City Toronto Wants to be?

What’s next for our waterfront? Well, allow me to get controversial. Call me an effete, latte sipping, bike riding, downtown elite commie if you like but the Gardiner threatens the kind of city Toronto wants to be. We’ve decided that Toronto is a waterfront city and we’ve spent more than half a century trying to make that a reality. Yes, we’ve seen that waterfront redevelopment brings in activity, money, and tourism. But I think there’s another angle to the whole thing. Central to the story of our waterfront redevelopment is an attempt to change the city’s identity.

A Transitional Space

The Gardiner chains us to the world we’ve spent so much time trying to escape. Few waterfront residents would pretend that the Gardiner is anything but an eyesore. To get to the water you find yourself dodging cars cruising along a crumbling concrete bridge built in the 50’s. This isn’t LA, our winter city is not kind to massive concrete structures. Moreover, the Gardiner remains a transitional space, a place to pass through, not to live in. This is completely opposed to modern city planning; urban space is for living. Highways were built to take people away from the city so that it could remain a site of industry without asking white people to live near it. Centering life around the car of course fueled the auto-manufacturing industry. Harbour City on the other hand, was built in direct response to the concerns raised by the car-oriented suburbs the highways spawned.

Spending 44% on the 7%

Many, including former city planner and one-time mayoral candidate Jenifer Keesmaat have called for us to put the Gardiner on the street level. It’s not just identity politics, the Gardiner isn’t just a symbol, and it doesn’t just spoil a walk to the water. The Gardiner is the most expensive item on the City of Toronto’s 10-year capital budget, taking up 44% of the money allocated for infrastructure projects over the course of ten years. Only 7% of commuters use the most expensive thing on the budget. Had city council voted to move the Gardiner to ground level in 2018, we would have saved half a billion dollars that could have been put towards transit. But for some reason, we can not disrupt the 7%.

ADVERTISEMENT |

Putting the highway on the ground, would on average, increase commute time about by about three minutes. With minimal impact on a seldom used traffic artery, massive savings, and fulfillment of our image change, putting the Gardiner on the ground was the most sensible option. Had we funded transit with the savings, we may have given that 7% an alternative way to get downtown, eventually unclogging the road for the diehard motorists. Naturally, we chose a compromise that satisfied no one. At great expense have we decided to knock down the portion of the Gardiner covering a section of shoreline we spent little time redeveloping while we maintain the Gardiner’s most obtrusive section. Toronto continues to be presented with so many opportunities to excel and we keep missing them.

The Questions Nobody Can Answer…

Why are we like this? We spend so much time and money trying to make Toronto a waterfront city, why not go all the way? What is Toronto? Is it a lakefront urban community? Is it a collection of suburbs connected by highways? Who speaks for our city? What do we really want to be?