“I never could have imagined that the Obama poster would do what it did,” says Shepard Fairey of his iconic HOPE poster. The famous portrait of the P.O.T.U.S. is arguably the most influential art world image of the 21st century, mostly thanks to its place in American politics and social media revolutions – but I don’t have to tell you that. If you’re reading this, you were there.

44-year-old Fairey is good-looking; he’s the kind of good, clean look Andy Warhol championed in theory but not style. This is perhaps rude of me to mention but Fairey’s recognizable face is at the seemingly opposite end of the spectrum to his friend Banksy’s constructed anonymity. The two artists are both living brands with PR teams, and multimedia projects, so it’s arguable that a negative image is just as potent to the cult of celebrity and iconography as the physical face. “Some of the street artists are anonymous because they don’t want to get in trouble; others are anonymous because it’s better for their image. It’s a much better selling point,” insists Fairey, who didn’t exactly expose himself in a conscious campaign for facial recognition. It just happened. By contrast, Banksy embedded anonymity – his image or anti-image, which are one and the same – into his art and brand. “Banksy’s made the joke that he’d be a disappointment to 15-year-olds who are fans of his work, and that’s coming from a very sincere place. How many times have you seen a movie and thought, ‘That sucked compared to the book?’ The book was your own projection, your own fantasy. How about all this Fifty Shades of Grey casting controversy…?”

“Banksy’s made the joke that he’d be a disappointment to 15-year-olds who are fans of his work”

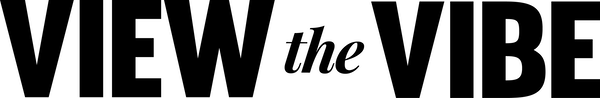

In this case, seeing “the original” Fairey in the flesh is as demystifying as seeing the pores of a Hollywood starlet or the disappointing size of the Mona Lisa. I’m used to it. I’m more surprised he’s in just a dark grey T-shirt and black pants — both noticeably devoid of iconography. I suppose I didn’t expect the graphic designer, social activist, and street artist to clad himself in clothes from his mainstream fashion label, Obey. I’m not sure why. Would that be gauche, at least for a 44-year-old man? Or because maybe it is simply a business venture, the same way I’d never actually expect to see Sophia Vergara wear her Kmart label on the talk show circuit. It’s not exactly high-brow social commentary on his Obey items, but the brand is still tied to the famous anti-conformity guerrilla street art campaign of the same name – from his younger days as a provocateur. The clothing brand, however, sells at mass market chains like Urban Outfitters, a retailer so good at serving up dead signifiers it makes them almost beautiful. The purveyor of plaid even managed to take the disregard for symbolic appropriation of hipster aesthetic and deaden it further, stripping it of its purposely misunderstood origins in second-hand Williamsburg. It was quite a feat for any of us who work in the industry. I know this. I judge this, I picked through it, but I still buy stuff there.

ADVERTISEMENT |

“I looked at the messages I put on T-shirts as a way to engage with people who don’t pay attention to street art, don’t live in a city where I’ve done street art, or don’t pay attention to what’s going on in galleries and museums,” insists Fairey. “Having my website on the label might be a point of entry for a whole world they haven’t considered. I can’t stand top-down elitism or elitism from the margins – underground elitism, like, ‘That used to be cool when only five people knew about it.’ If I lose that person as a fan, I don’t relate to that person anyway. Good is good. I’m a populist. I want to be accessible.”

Under the table, I find his first obvious brand allegiance in the Adidas stripes on his shoes. Given his brand collab resume, there’s a strong chance he could have designed them too. While Warhol’s relationships to brands and celebrity pervaded his time and made the art critics question themselves, Fairey infuriates his detractors. It’s hard to tell if he’s infiltrating the mainstream to make money, social commentary, or both; it’s sometimes hard to ascertain if he even knows what’s what. Either way, calling him a sellout in rebel’s clothing means you haven’t entered the vortex of brand implications in contemporary culture. He’s been called everything from the voice of a generation to “Hello Kitty with more pretensions” by art critic Christopher Knight.

“I’m a populist. I want to be accessible.”

Right now, Fairey’s casual T-shirt attire is the most rebellious thing about the street artist’s current surroundings. The brand-sponsored media lunch is always a curious event, with roundtable-style questions often leaving journalists resenting each other’s attempts to dominate the conversation, exposing our desperation in the presence of fame, or knowledge that it’s a good story. If Fairey’s here to promote a limited-edition bottle for Hennessy that he designed while we ask the so-called daring questions about selling out, we’re going to use the article we write to get paid, show off our skills, and generate ad revenue for our respective publications. We’re a part of the system he’s accused of compromising his artistic integrity for, and while it would be easy to say we’re not the ones trying to be artists here and we all know Fairey doesn’t exactly need the money, that’s overlooking an important point: none of us would be writing a story about Shepard Fairey today if he didn’t mix business with artistic expression so conspicuously. There’s not a single high-brow art critic among us, but I recognize a well-known fashion editor and music writer at the table. This lunch will spawn everything from light pop culture stories to politically-charged pieces, and Fairey’ words, ideas, and art will once again infiltrate daily newspapers, weeklies, magazines, blogs, and websites with vastly different audiences.

ADVERTISEMENT |

I’ve heard people use the term “famous for being famous” when referring to Fairey but — in the online era where revolutions often begin with a hashtag on Twitter– an artist’s level of renown plays a more central role in his cultural currency than ever before. It’s easy to see mass market appeal as a negative thing in light of American artists who come from the capitalist consumer culture we reflexively think of as evil, but international art figures like Ai Weiwei — who make art that is accessible in both meaning and place/space in order to incite social and political change — have shaken up the game for everyone. The age-old question “but it is art?” seems dependent on the answer to “is it revolutionary?” When Marcel Duchamp introduced the concept of the ready-made in the early 20th century, he boldly showed that even the most skilled painter used commodities like manufactured paint, canvas and brushes just to create yet another commodity for our commodity-obsessed industrial world. Perhaps in the globalized 21st century, the revolution is the masterpiece — the art just the tool to fuel the movement.

It’s easy to forget the provocateur side of Fairey at a brand-sponsored round-table interview, where the rebel rousing comes from the odd journalist who decides to speak out of turn just to get in an extra soundbite from the artist. With no one-on-one atmosphere for natural conversation flow, questions get a clockwise rotation, and the PR reps referee the table talk. Fairey’s personal manager sits to his immediate right, smartphone at hand. To his left, more journalists from select big-name local publications. Public relations and marketing reps from Hennessy bookend the Last Supper-esque scene at the heads of the table. Three cognac bottles designed by Fairey sit in the middle. When Fairey gets politically charged in conversation, he goes off on impassioned tangents about Obama’s drone program and domestic government spy initiatives — clearly something he’s been asked to steer clear of. I don’t know if the signature “Revolution” cocktail is meant to be ironic, or if Fairey intends for me to wonder this at all.

Even a – literally – watered down image of revolution can’t take away the fact that Fairey’s Obama poster is the most iconic image of the 21st century, thus far. I’d rather have one gold medal than 50-odd silvers and bronze emblems of almost scratching the zeitgeist but not quite being “it.” If Obama was relying on the youth vote in 2008, having a campaign image made by a then little-known, but highly-respected, guerrilla street artist who represented a generation’s distrust of authority through an aesthetic that pleased them could only make him the most obvious choice for a brand new American way. “I wanted to cultivate the interest of people who thought, ‘You know, this guy is interesting to me, but now I have a symbol to latch onto.’ Or maybe the symbol itself is the thing that made them look deeper into [Obama] as a candidate,” insists Fairey. “That ended up working far beyond my belief. Every time I make a piece, I’m thinking of the best balance of saying what I want to say in my style but also making sure that it’s relatable.”

“Every time I make a piece, I’m thinking of the best balance of saying what I want to say in my style but also making sure that it’s relatable.”

The original now hangs in the Smithsonian. The pop-art and Soviet-constructivist-inspired poster was based in part on the Che Guevara two-dimensional portrait, a symbol of revolt commoditized and stripped of its original meaning. Whether the HOPE poster was meant to stand in contrast to that (because it was free for download and was an actual call to action for the American people), or if it worked because it appealed to a generation who’d bought the Che image from Urban Outfitters, it’s hard to say. Perhaps it did both. The social media demographic not only put up posters and made T-shirts, but they also made it their Facebook profile picture and Twitter background.

ADVERTISEMENT |

After Obama was sworn in, Fairey’s fate had changed too. He had a choice: renounce the perks of celebrity, or use them – along with the exclusive platforms of name recognition status – to infiltrate culture. He made like Warhol and chose the latter. “I’d argue that he’s one of the most influential artists in the world, and not just because of monetary reasons but because of the social currency that he has – design firms, the professional work he does for corporations, as well as the street work, the fine art, and the clothing line,” says art critic James Daichendt on the phone from California. “I see it in surf shops and I see middle schoolers wearing it waiting for the bus. That kind of platform leads to interesting discussions, positive and negative.”

“After Obama was sworn in, Fairey’s fate had changed too. He had a choice: renounce the perks of celebrity, or use them”

Fairey branded Toronto this week with an iconic Fairey logo on the back of the Gladstone Hotel and on the side of Tattoo Bar on Queen West. Neither were the work of a graffiti artist genuinely inspired by the city; the two murals were part of Hennessy’s world tour with the artist, and Toronto’s not a place he knows particularly well. If they’re watered down versions of what he used to do, my phone is nevertheless lighting up with notification of comments and likes on the image I posted of Fairey and me on Facebook while at the event. Even my best friend, who can’t be bothered to go to art museums on vacation, knows who he is. And to be fair, when asked by another journalist if he has a favourite Toronto artist, Fairey is quick to say, “Gary Taxali.” It turns out he even wrote a foreword for his friend Taxali’s book, I Love You, OK? If he doesn’t know Toronto well, he’s certainly familiar with the international art scene, and also cool and considerate enough to support his contemporaries’ work.

ADVERTISEMENT |

Daichendt is the first art critic to write a full retrospective on Shepard’s art and brand, aptly titled Shepard Fairey Inc. If the Obama poster had made him famous, he’s already repurposed the image to criticize that same president’s government as a visual emblem for Occupy Wall Street, for instance. He has also made a cult around his signature – be it on a wall or by a paying brand collaborator. “When you go to a Shepard Fairey exhibit, it’s crammed, there’s a line, and there are people around the corner waiting for hours,” insists Daichendt who spends a lot of time visiting galleries for his work, and the showcases usually have a generic flow with a predictable vibe and fluid amount of an expected audience. Fairey exhibits make art exciting. “He’s inside DJing, and there are lines inside, but then they’re giving away things at the same time. It’s more than an event – it’s a happening. There’s an excitement to how he’s showing his work and what he wants from his fan and collectors – the very fact that we call them fans. He’s a shot of adrenaline to the art world.”

Perhaps if everyone understood Shepard Fairey, then he couldn’t be Shepard Fairey. As much as the people who called the cops on him were integral to the spirit of his early street art, perhaps his antagonists and critics are necessary to his relevance now. Fairey’s manifesto has always been to incite people to question authority for themselves, and to promote a large-scale dialogue. Now Obey Clothing is the exact kind of corporation his Obey street art campaign asked people to question: What do these symbols mean, if anything at all? No matter what people’s opinions on Fairey’s art and life are, what’s important is that we’re all paying attention. If he’s cashing in on the “revolution,” as many critics want to believe, he did so in part to build a giant megaphone — a cultural megaphone so big, he could say anything and we’d be listening. And if the Obama poster is an indication, he’s not waiting for us to obey; he’ll capture a movement if we make it. That responsibility, at least, is on us.

ADVERTISEMENT |

If you liked this article, check out Vicki Hogarth’s Vv Magazine feature on Canadian politics, Life After The Mayor Election: Why Canadian Politics Still Matter.