I’ve found that one of my favourite things to tell someone who hasn’t lived in Toronto for very long is that Yorkville was once the centre of the city’s countercultural scene. They’re usually surprised. Why shouldn’t they be? Yorkville is almost unrecognizable from The Village of 60 years ago, and the neighbourhood is mostly condominiums and boutiques. How did the centre of Canadian youth become a yuppie oasis?

RELATED: Toronto is Getting a New Beach: Leslie Slip Lookout Park >>>

Gerrard Street

The story of Yorkville actually begins on Gerrard Street, sometime in the early 1950s or late 1940s, depending on who you ask. Like many sections of downtown, Gerrard Street was emptied out as much of British Toronto migrated to the suburbs. This opened up the area for Eastern European immigrants. With them came the coffee house culture that gave the city (known for its strict liquor laws) a place to exist outside of home, work, or school. Bohemian Gerard Street was not meant to be, and the bourgeoning scene was torn down for an expanding Toronto General Hospital.

ADVERTISEMENT |

First Steps in Yorkville

Many artisans, shopkeepers and café owners migrated north to Yorkville, a former Victorian village and then rundown Toronto annexation. Like Gerrard Street, many of Yorkville’s British residents died or moved on. This left the Victorian rowhouse available for anyone looking for an affordable and romantic place to live. By the mid-fifties, the neighbourhood had welcomed antique shops, various professional firms, a couple of interior decorating stores, and the Lothian Mews shopping complex. What I want to emphasize here is that we can’t look at Yorkville as a monolith. While the neighbourhood had its fair share of music venues and hippie hangouts, middle Toronto had a strong presence from the beginning.

The music scene

For the more nostalgic, the music scene at Yorkville remains the centre of attention. When coffee houses moved from Gerrard to Yorkville the owners of venues like The Half Beat, The Purple Onion, and the 71 Coffee House began to cater to the nascent folk movement. Artists like Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Joni Mitchell found audiences of young, and curious Torontonians, hungry for a more authentic kind of music. Bigger sites began to open and places like, The Riverboat Coffee House gave a start to Gordon Lightfoot and hosted big names like Simon and Garfunkle. As tastes began to shift to Rock and Roll, new clubs such as The Embassy and Brave New World sprung up for newcomers Neil Young and Rick James. Yorkville had become the centre of Canadian music.

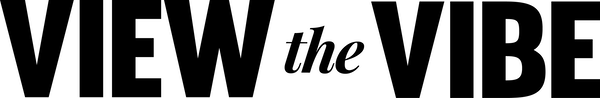

Life in Yorkville

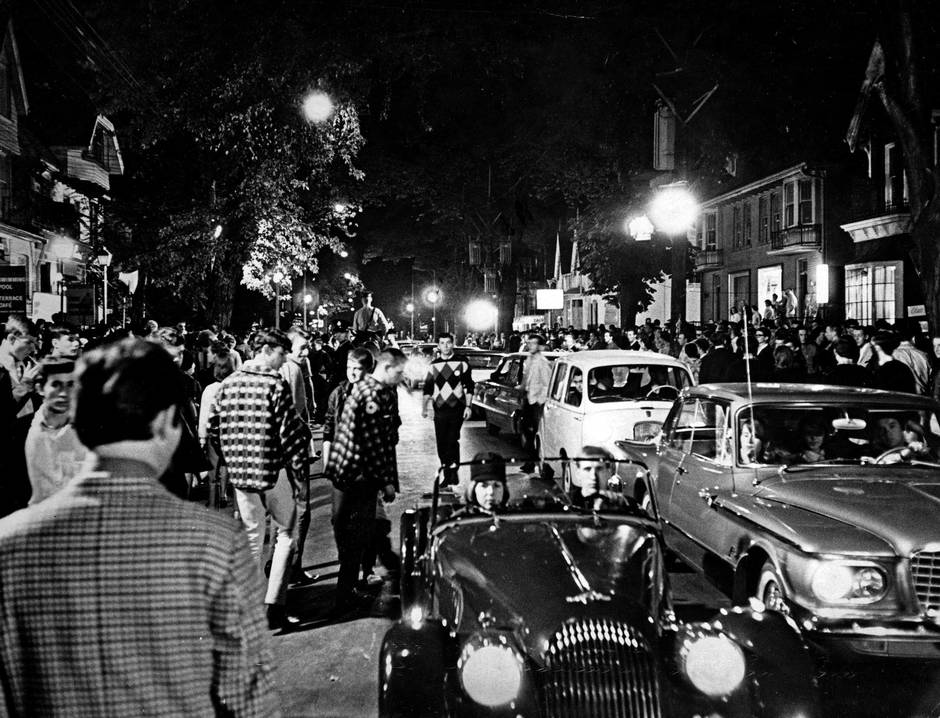

Within the music scene was an attempt on the part of mostly teenagers and twenty-somethings to figure out another way to live. Most of the early villagers were disaffected with the 9 to 5, suburban, nuclear family lifestyle they had grown up in and wanted a more communal kind of living. For them, Yorkville was a place to be free from work and boredom. For some of the more vocal residents, life in Yorkville was a political statement, a rejection of commercialism, and traditionalism. And for latecomers, Yorkville was the last place they could go, having run away from poverty or abusive homes. In the end, it was a place for young people to live on their own terms.

The centre of moral panic

So what happened? The first problem was drugs. Many of the early residents began experimenting with hallucinogens as a part of a broader cultural movement. This movement sought to use drugs like marijuana to explore the mind, introspect and elevate the consciousness. By the end of the 60s however, the drug culture had shifted. New villagers were younger, and often with unresolved mental health problems. Addiction and overdoses became serious and Yorkville, long since considered a problem by middle class Toronto, became the centre of a moral panic.

ADVERTISEMENT |

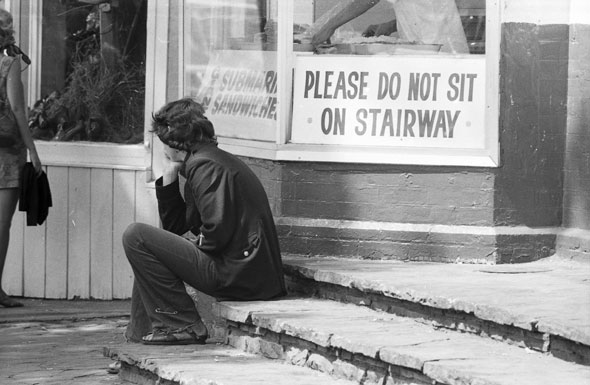

The Anti-Yorkville Movement

Enter Allan Lamport. Lamport, who wore many hats in Toronto politics, really distinguished himself as the voice of anti-Yorkville Toronto. Lamport made a point of making a counter-statement whenever Yorkvillians protested something. Wanting to get rid of the neighbourhood entirely, Lamport, or “Lampy” as he was known, pushed to assign each of Yorkville’s youths I.D. Cards, and eventually bulldoze the whole neighbourhood. He hoped that it would become a shopping district.

Eventually, he invited a group of Yorkville activists called the Diggers, led by the charismatic David DePoe to a “talk in” at city hall. He hoped to make a show of him straightening a bunch of kids out. What started as an informal debate turned into a weeklong protest along Yorkville Avenue. The protestors aimed to cement the neighbourhood as a place for the young. The police, a constant presence in Yorkville, made multiple arrests. Though Yorkville was a hub of drug busts and police activity, this police crackdown was particularly brutal. In light of all the broken bones, The Canadian Civil Liberties Association called for a royal commission. This would not be the last protest over the fate of Yorkville. While looking up at the modern condo buildings, you can’t help but know who won that fight.

The new Yorkville

There aren’t any more hippies in Yorkville and the music scene is basically gone. The shop viewed the hippies as threats to their business and welcomed development and a more middle-class environment. By the late 60s, most of the hippies had moved onto Rochdale College, an experimental campus and residence at the University of Toronto. There, students had no traditional classrooms or homework and few rules. Yorkville had become much less attractive. People had become much more concerned with drugs, they were less of a gateway to a higher mind than they were an addiction. For all intents and purposes, Allan Lamport won.